BOLD WOLVES Summary of the 2022 international conference

On 29 April, at the Fortress of Bard, took place the second thematic conference of LIFE WolfAlps EU focused on bold and urban wolves. An in-depth examination of the cases ascertained in Italy, France, Slovenia and Germany, and the management guidelines. Several experts took part as indicated in the programme, including Piero Genovesi, head of ISPRA’s Wildlife Coordination Service, Ilka Reinhardt, from the Institute for Wolf Monitoring and Research in Germany, Valeria Salvatori from the Institute of Applied Ecology, the scientific coordinator of LWA EU Francesca Marucco and the project partners Nolwen Drouet-Hoguet from OFB and Christian Chioso from the Valle d’Aosta Region.

The afternoon was dedicated to a round table to discuss the problem of bold and urban wolves together with the mayor of Arvier, a village in Valle d’Aosta where cases of urban wolves have been , and representatives of hunters, breeders and environmentalists.

In this article we give a brief summary of what emerged during the meeting.

What is a bold wolf?

A bold wolf is a wolf that is strongly tolerant to people, is not afraid of them and approaches people directly and repeatedly on foot, at a distance of less than 30 m. This is the definition given by the experts of the Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe (LCIE), a specialist group dedicated to Europe’s large carnivores.

However, the presence of a wolf in an human-dominated landscape, i.e. a wolf crossing roads or passing by houses does not imply a problematic behavior, it depends on how the wolf relates to people. Wolves (and other animals) that habitually frequent urbanised contexts are in fact defined as urban.

In an increasingly human-dominated world, it is inevitable that some animal species will adapt and use areas where the human presence is more widespread. It is mainly the more opportunistic species, those able to exploit the most diverse contexts to survive, that are able to adapt to urbanised areas.

In more natural contexts, where human density is low or absent, wolves (and wild animals in general) rarely visit human settlements, except on specific occasions, for example when heavy snowfalls in winter bring ungulates down the valleys. In areas where there are many roads and human settlements it is almost inevitable that animals will have to deal with human presence.

This is true for young dispersing wolves, looking for a place to settle in, as it is for the territories of some packs. Certainly, it is unavoidable in human-dominated landscapes (Po Valley in Italy or Saxony in Germany) where the species has been returning in recent years. In such these, it is therefore inevitable for a wolf to occasionally cross or pass by villages. In fact, most animals try to avoid direct encounters with humans anyway: if they cannot avoid man-made places, they roam at night when it is more difficult to encounter people.

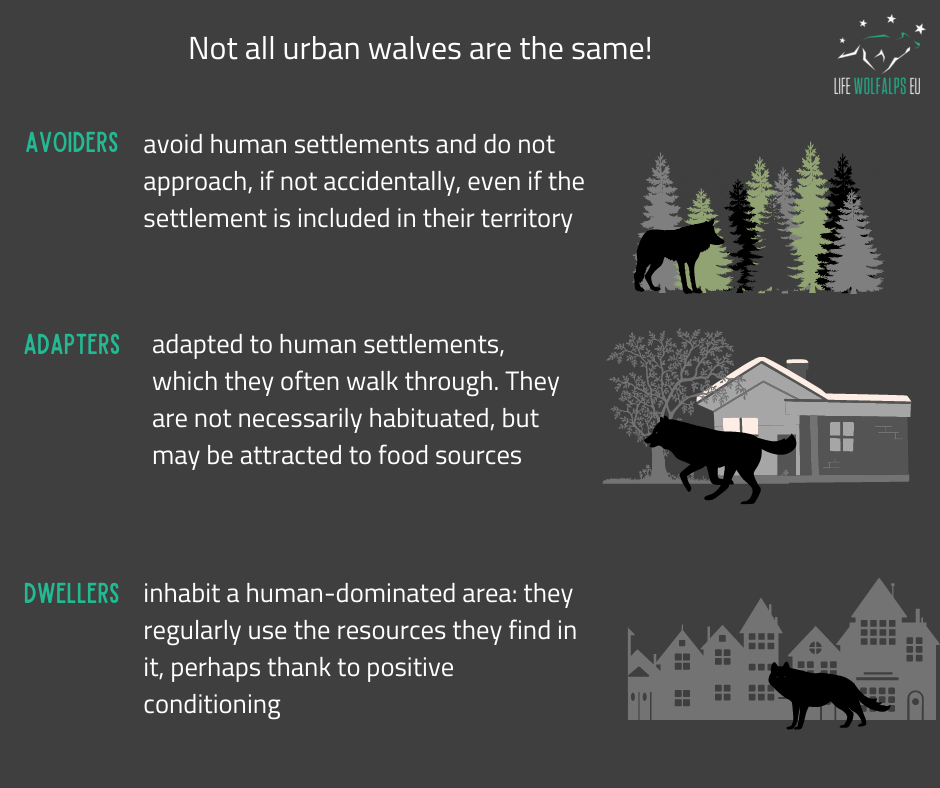

Animals that avoid inhabited areas, or occasionally pass through them in special situations, are called urban avoiders.

On the other hand, some individuals are able to take advantage of the resources offered by an urban environment and adapt to it (urban adapters) by frequently frequenting it, but still dwelling in natural contexts. Finally, there are the urban dwellers who live within the urban landscape. Among canids, there are foxes and coyotes that have adapted to live their entire lives in large metropolises, while wolves frequent small urban centres or rural settlements.

When does a wolf become bold?

A fundamental condition of bold behaviour is strong habituation. This is a learning process whereby an animal becomes accustomed to repeated stimuli, which, in themselves, have no positive or negative consequences. Bold wolves are accustomed to the presence of humans.

This level of adaptation is not problematic if wolves tolerate people, their structures, vehicles and activities at a certain distance without taking any direct interest in people themselves, always remain at a certain distance, In fact, wild animals living in man-made landscapes are somehow forced to develop a tolerance towards noise, vehicles, lights etc…

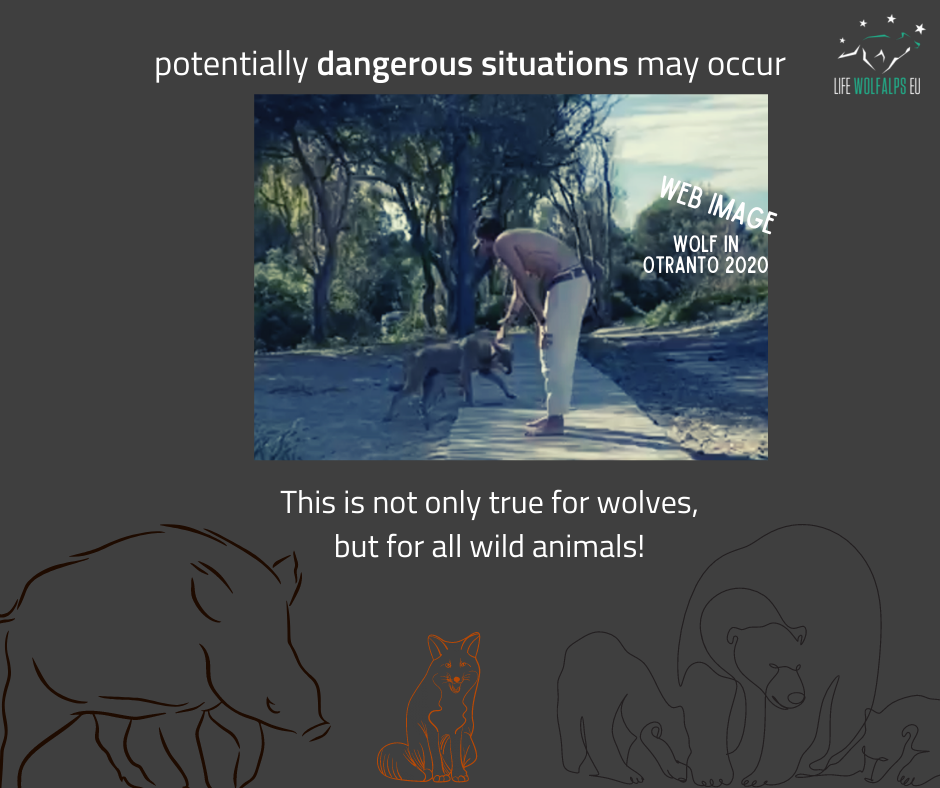

However, habituation is an adaptive process and when it is strong, i.e. when wolves tolerate the presence of people at close range, this is a behaviour that can become problematic and dangerous. Such strong habituation is often linked to positive conditioning, i.e. a behaviour is reinforced because it is associated with some sort of reward. In particular, food conditioning is a form of positive conditioning in which animals associate the presence of humans or places where humans are present (e.g. campsites, backyards) with the availability of food. This is why it is important to ensure that wolves (and wild animals in general) do not find food availability when they come into contact with an urban context.

Wolves are animals capable of adapting to different environmental contexts, modulating their habits and behaviour. In anthropised contexts it is often difficult to assess whether the wolf is behaving normally or in a problematic way that requires management intervention. This is the purpose of the LCIE guidelines, which provide managers with a key to understanding the different behaviours of wolves and the recommended management actions. For a correct evaluation it is of great importance to document the case and to archive the collected data in order to refine the knowledge of the problem over time and thus guide the application of interventions in an increasingly effective way. In this regard we would like to mention the document produced in the context of action A7 of LIFE WolfAlps EU, the Management strategy of bold wolves at the alpine scale.

Documented cases

The conference on 29 April was an opportunity to verify the situation in Italy, France, Slovenia and Germany. What emerged from all the reports is that cases of confiding wolves are rare.

In Italy, as reported by Genovesi from ISPRA, there have been 23 cases of confiding wolves over the last ten years. Reports come from all over Italy, and there has been an increase in reported cases since 2012. In Slovenia, from 2006 to 2022, 3 cases have occurred, as reported by Černe and Simčič of the Slovenian Forest Service, and 2 cases have required management intervention in Germany in 22 years, as reported by Ilka Rehinardt, author of a document on bold wolves.

In France, the OFB carried out a study (available here) in which the behaviour of wolves when encountering people was analysed. A total of 3280 encounters have been analysed that took place between 1993 and 2020. In these 30 years the number of encounters, even at a distance of less than 50 metres, has increased along with the population growth. What has not changed, however, is that throughout the period under consideration, the main reaction is one of fear and flight (77% of cases overall). However, the number of cases in which the wolves show indifference or move away slowly has also increased over time. Out of 3280 encounters, 10 are those in which the wolf showed aggressive behaviour towards people, and in 9 of these it was a defensive reaction from what was perceived as threatening behaviour. No attacks were reported.

In some cases, wolves that allow themselves to be approached are animals in distress or young individuals. For example, in Pragelato (TO), in 2015 an elderly female wolf spent two days in the middle of houses, sleeping on a doormat. In those days there had been heavy snowfall, and the animal had been chased by a car on the road as far as the village. Exhausted and unable to move in the deep snow, the female (which genetics later revealed to be an old female, once the dominant of a pack that never frequented built-up areas) stopped in the village, but left it after two days, as soon as she recovered.

Given the strong personality of wolves and the wide variety of contexts, all experts agree that a case-by-case assessment is necessary. Therefore, once a report of abnormal behaviour is received, the authorities have to activate the collection of information necessary to define the intervention. The LCIE guidelines taken from the strategy produced by LWA EU provide a classification of behaviours, their assessment and suggest the most appropriate action to be taken. A fundamental aspect is the verification of the presence of attractors and their removal, also through an ordinance.

If, in spite of these interventions, the wolf continues to show confident behaviour, a further level of intervention will be evaluated. In Italy, as Genovesi explained, capture, translocation and removal interventions can be requested as an exception to the Habitats Directive and require an authorisation process that includes the opinion of ISPRA and the authorisation of the Ministry for Ecological Transition.

Concerning the case of Arvier, a village halfway between Aosta and Courmayeur. In November 2020, photo-traps set up for wolf monitoring had spotted wolves moving in a restricted area where the municipality of Arvier is located. In January and February 2021 wolves were frequently sighted within the village. In two cases, a deer and a roe deer were preyed upon within the village (to be precise, the carcass of the latter was found in the courtyard of the primary school). In order to try to understand what was happening, monitoring in the area was intensified both with photo-traps and night-vision goggles. Intensive monitoring verified that three wolves were frequently crossing the village, both at night and during the day. Their frequentation lasted until March 2021. The genetic analyses obtained from the intensive monitoring made it possible to identify the three animals frequenting the village: a pair and a male. In May, regional law 11/2021 (Measures of prevention and intervention concerning the wolf species. Implementation of Article 16 of Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora), which stipulates that, subject to ISPRA’s opinion, the Valle d’Aosta region may capture and remove a single wolf, after checking that there are no alternative options. The Region then transmits directly to the State all the information for the compulsory report to the European Commission, according to the Habitats Directive.

In December 2021, observations and reports of wolves in the village by the inhabitants of Arvier began again, with visits also in the morning. The Region then sent a detailed report to ISPRA on the situation. According to ISPRA’s indications, monitoring has been intensified, and at the same time an information campaign has been launched to inform the inhabitants on how to behave. ISPRA also recommended that at least one animal be radio-collared, and that acoustic and light deterrence be provided (the radio-collar is important because it makes it possible to check the effectiveness of deterrence). On 16 March, a bleeding wolf was reported near La Crête, a village south of Arvier. The animal was recovered by the Forest Service and taken to the wildlife rescue centre, where the injuries were found to be minor. After a short stay in hospital, the animal was released with a radio collar, which allows its movements to be monitored. As suspected, it is the single male that frequented Arvier (M33). The data collected will thus make it possible to understand the territory occupied by the animal, and to better understand how to intervene.

To view the conference click here.